The other day my friend Andrew messaged me out of the blue:

--all-servers By default, when dnsmasq has more than one upstream server available, it will send queries to just one server. Setting this flag forces dnsmasq to send all queries to all available servers. The reply from the server which answers first will be returned to the original requester.

Rather than finding it odd to receive a pasted chunk of a manpage via IM, I was fascinated by the content. By configuring dnsmasq to be a slightly obnoxious netizen, you can effectively always have your queries answered by the fastest server — whatever it happens to be for that query.

What I wondered was how big of a difference it would actually make. Would there be a measurable difference? 5%? 20%? I decided to take namebench for a spin and find out.

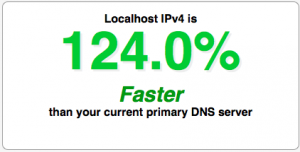

The results left me so incredulous that I disabled dnsmasq’s cache entirely, figuring that it was maybe giving it an unfair advantage. (Though I don’t think it is — all my upstream servers are running caches.) Re-running with dnsmasq being forced to go upstream for every query, it still ended up 124% faster than the next-best choice. (Wat?!) It strains belief, but see for yourself:

dnsmasq running against the 5 resolvers in my /etc/resolv.conf, using the --all-servers flag, had a mean response time of 32.00 milliseconds. (Yes, that’s curious even, but the fastest was 12.2 and the slowest was 666.7, so I don’t think 32.00 holds any special value.) namebench compared it against my current nameserver, my ISP’s local nameserver, which averaged 71.68ms. (It had the same 12.2ms minimum, and the worst case was 3.5 seconds.)

In fairness, namebench found a couple of servers that are slightly faster than my ISP’s, and dnsmasq wasn’t 124% faster than them. But it’s still a huge improvement. The fastest is another of my ISP’s servers, with an average of 53.65ms. Level 3’s 4.2.2.1 open resolver averaged 60.48ms, OpenDNS averaged 69.21ms, and Google’s 8.8.8.8 averaged 75.82ms.

What’s interesting to me here is that, by asking multiple servers and always returning the fastest, dnsmasq with –all-servers ends up being considerably faster on average than any single server. It averaged 32.00ms, while the next best one averaged 53.65ms. And bear in mind that this is with dnsmasq’s cache disabled because I worried that it would bias results in favor of dnsmasq.

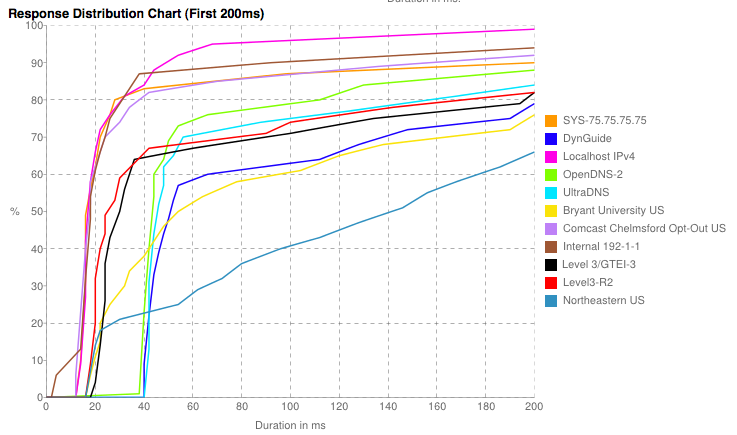

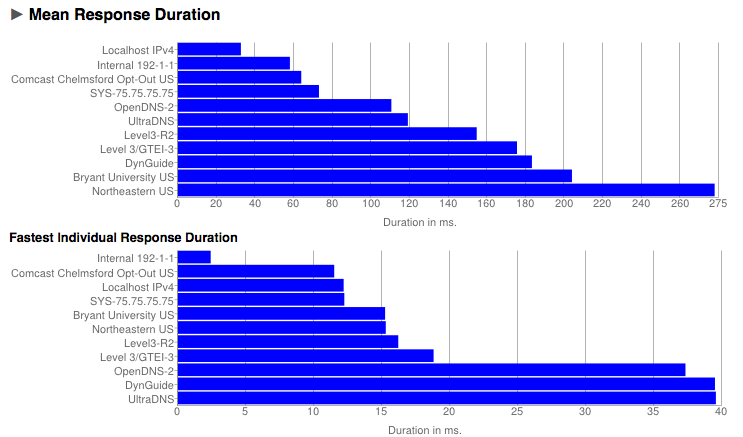

Graphs, for those who love them:

(Don’t mind the “Internal 192-1-1” entry — it’s a broken internal DNS cache that slipped in erroneously. It shouldn’t be used much on the LAN and uses Comcast as its upstream, so the fact that it’s slightly faster than Comcast suggests that there was some room for caching here.)

Recall, too, that this is with caching disabled in dnsmasq! It had one hand tied behind its back and it still won by an incredible amount.

For what it’s worth, here’s my dnsmasq.conf:

port=53 domain-needed bogus-priv resolv-file=/etc/resolv.conf interface=lo0 listen-address=127.0.0.1 no-dhcp-interface=127.0.0.1 cache-size=0 no-negcache bogus-nxdomain=67.215.65.132

Take note that you should not use the “cache-size=0” or “no-negcache” entries — they hurt performance. (And very badly in the real world!) I included them only to rule out the possibility of dnsmasq being faster because it was working from local cache. Of course, you really shouldn’t blindly copy-and-paste this, and it’s a very vanilla setup.

I ran dnsmasq in the foreground with sudo dnsmasq -d --all-servers.

What I’m wrestling with is the question of whether this is such poor “netizenship” that it’s bad practice. With --all-servers set, dnsmasq will send a copy of your query to every nameserver in /etc/resolv.conf. That’s five entries for me, effectively increasing load on DNS servers five times. That’s pretty obnoxious. (Though having five entries in /etc/resolv.conf is unusually many.) But at the same time, perhaps the biggest advantage of dnsmasq isn’t its borderline-magical --all-servers flag, but that it’s a caching resolver, which helps reduce the number of DNS queries that make it out of your network. So perhaps the impact isn’t quite as bad as it might seem. And in an ideal world, you’d only hit the your ISP’s servers, or a free service like Google’s or OpenDNS’s public servers, which would answer out of cache. So it does feel a little selfish and like a tragedy of the commons, but I don’t think it’s actually overly harmful.

1 Or something like that. I don’t actually have a transcript of the conversation.

Thanks for the test.

I would still consider it bad netizenship because it trashes the individual caches if more people start doing it.

The normal way is, libc chooses the first (first to answer, not sure) from /etc/resolv.conf, and sticks with it. So this resolver does the caching for this client from that point on. In most networks, the cache of the name server is populated with entries common for the users of that network. It could be used for DNS-Amplification-Attacks, if the dnsmasq server is reachable for the bad guy. Even worse, if more then one dnsmasq server is chained.

So my suggestion is: If your provider is offering more than two name servers, test them, and choose the one fastest for non cached queries (there). B/c it seems to be fast, and you get the RAM and cache for free (without paying energy). If you notice one of the servers holds all the cache of your queries, then you’re fitting in with your usage, choose that, it is even faster for you (as you might use the same gTLD, ccTLD as the other users.

does that make sense for you?

Matthias

What I had actually intended, but didn’t really make clear in my post, is that this is something you’d run as a DNS server for a small LAN. I just used localhost because I didn’t have a spare box to set this up on at the time. It would be wasteful, as you say, to run this on each box on a network, and dangerous to run it on a public server. But for a small LAN, I think it’s ideal — it will develop a local cache, and cache misses will get answered quickly and then cached.

It seems (based on my observations, but not any great experience with the code) like the way libc works is that it always uses the resolvers in order. If the first entry in resolv.conf is invalid, name resolution will be delayed several seconds.

This is exactly as most libc implementations work today, which is stupid, because there are a few other implementations, that take answer time into account (some MTAs have that, for it’s own resolution).

If I would know better C, I could implement it, but so I can only write about it, time to get back learning ;)

Pingback: A Tale of Two Servers | ma.ttwagner.com

Pingback: CrossBreeder - Forum Android Italiano

Pingback: Use Getflix or Unblock-Us servers selectively with Dnsmasq | i reckon

Can You update this tutorial on how one can use the “–all-servers” flag inside the /etc/dnsmasq.conf file ?

Do like this

all-servers

Good question! I had it too. But yes it’s on the man page:

At startup, dnsmasq reads /etc/dnsmasq.conf, if it exists. (On FreeBSD, the file is /usr/local/etc/dnsmasq.conf ) (but see the –conf-file and –conf-dir options.) The format of this file consists of one option per line, exactly as the long options detailed in the OPTIONS section but without the leading “–“. Lines starting with # are comments and ignored. For options which may only be specified once, the configuration file overrides the command line.

Hi not sure but i think what all-servers does is not using the servers simultaneously from /etc/resolv.conf but the servers you add in dnsmasq.conf similatenously , like

all-servers

server=1.1.1.1

server=8.8.8.8

Will make it ask both 1.1.1.1 and 8.8.8.8 at the same time

regardless what you have added into your resolv.conf file

However i might be wrong

We have an instance of dnsmasq configured (using /etc/dnsmasq.conf) on our server along with a few upstream name servers to forward DNS queries to. We noticed that irrespective of whether the option all-servers was mentioned in the conf file or not, the packet capture showed that dnsmasq was forwarding the queries to all the name servers simultaneously. Can someone advise on what is being missed here?

Pingback: How the Internet Works: a Comprehensive Look | The Rubyist Blog

Mabosway substitute sites and mobile sports login friends – There are lots

of online gambling agent sites scattered on the internet.

Each of these sites has offers and features provided, including the types of gambling games available.

Many online gambling sites forlorn offer 1 to 3 types of games and entirely have

excellent games they offer.

Mabosway.com is an online gambling agent site that offers not lonely 1 or 3 types of gambling games but 7 interesting types of

gambling games that you can play. This proves that Mabosway is the most

solution betting site that offers not only online soccer gambling, but Casino, Poker, Toto 4D, Bola Tangkas, Fish Hunter and online cockfighting gambling.

This site is known as Mabosway Indonesia for members who

arrive from Indonesia.

Various types of online gambling games are thoroughly supported by the maximum encourage from Mabosway.com.

One of them is the Customer abet feature which is 24 hours standby

to utility buildup and invalidation transactions for members.

How to register is as well as simple to do, especially for beginner bettors who are

starting to bet for the first time.

How to Apply for Mabosway

How to register mabosway is definitely simple for unmemorable people who desire to begin playing online gambling.

You abandoned have to click the link NOW button upon the house page which will go directly

to the registration form page. After successfully registering you will get a user ID as an identity in the game.

After all is done, you are officially joined and become a member.

After you officially become a aficionado you are offered to choose the type of online gambling game that you can play.

Here are 5 types of favorite online gambling games that you can accomplish at Mabosway.com.